articles

-

A tip: if you use YouTube on mobile, try it in the web browser instead of the app. You get the conveniences of your web browser *cough*UBlock Origin*cough*, as well as the ability to continue playback while minimised — a paid feature on the app. This is great for turning YouTube interviews and essays into “podcasts”. ↩︎

-

Another tip: You can’t use RSS to subscribe to your Watch Later list as it is private, but you can create a new “bookmarks” playlist and subscribe to that, and use that list as an alternative Watch Later list that appears in your RSS reader. ↩︎

- Tech Won’t Save Us Paris Marx hosts this Neo-luddite interview podcast. Common topics include the environmental harms of tech, workers exploitation, and why tech billionnaires are bad for society, with a particular focus on Musk.

- This Machine Kills Luddite duo Jathan Sadowski and Edward Ongweso Jr host this discussion podcast, with occasional interviews, in-depth article reads, and discussion of economic trends within the industry.

- Trashfuture A British “techno-pessimist” comedy podcast that pokes fun at the absurdity of the current tech and political landscape. A regular feature is the main host picking a ridiculous/dystopic tech startup, reading some of their marketing blurb, and the co-hosts and guests have to try and guess what the product is.

- It’s super convenient. If you have an okay pair of shoes and a backpack, you’re good to go. For weight, you could use a book, a bottle of water, or one of the old bricks every British person has lying in their garden for some reason. I use a couple of weight plates wrapped in towels for comfort.

- The injury risk is very low. The impact on your joints is very small compared with running. In fact, my chronic pain feels better after a ruck.

- It’s perfect for “headspace”. Walking is so natural and doesn’t leave me completely breathless, so I can actually let my mind wander and just enjoy being outside with my own thoughts — while still getting a great workout. This is a serious benefit that should not be overlooked.

-

Pick a simple platform and create a blog. Don’t sweat this choice too much - they all do more-or-less the same thing and you can always migrate later if you don’t like your current choice. My recommendations:

- Bearblog (free for basic, $6/mo for the full package). For the absolute simplest and fastest way to start posting text for free, try Bearblog. I literally just signed up and made a post while I was writing this.

- micro.blog ($5/mo). This is the one I use. As well as blog hosting with cool features like the bookshelf, it provides a social media-style timeline for following and replying to other blogs.

- Scribbles ($5/mo). The newest platform on this list, Scribbles has a great non-markdown editor and makes it easy to discover other blogs on the platform via the explore page.

- Pika ($6/mo) is another great option if you don’t want to use markdown.

These small platforms are all ad- and tracker-free, and you own your own content, which is why there’s a fee - you’re not paying with yours and your readers' data. I read blogs hosted on all these platforms, they’re all great. If you don’t care about ads, trackers, and retaining full ownership of your content, there’s always wordpress.com or tumblr for free.

-

Sign up for Blaugust so other participants can find your site easily.

-

Start posting in August! And remember, no one actually gives a shit about your blog, so there’s no pressure to post something Good (advice I need to constantly remind myself of). Just get in the habit of posting. The Good posts can come later. If you’re stuck for ideas try some of these.

-

Get an RSS feed reader. RSS is how you can stay updated with other people’s blogs. It’s exactly the same technology your podcast player uses to subscribe to podcasts, but you can use it to subscribe to blogs and other sources. There are many good free and paid options on all devices, and it’s easy to move your subscriptions from one app to another. You can subscribe to my site by pasting https://samjc.me/feed.xml into your RSS reader.

- The Forest and The Factory by Phil A. Neel and Nick Chavez. Long, occasionally whimsical essay on a question that is often overlooked in utopian post-capitalist imaginaries — how do things actually get produced? In particular — how are things produced at scale? Neel and Chavez identify as communists, but even if you don’t like that word there is much to be learned here for anyone interested in imaginaries like eco-socialism, degrowth, social ecology, solarpunk and so on. Link to Chavez’s website

- Mother Trees and socialist forests: is the “wood-wide web” a fantasy? by Daniel Immerwahr. The idea that trees are altruistic and can share resources and information has gained a lot of traction recently, sometimes in eco/leftist discourse as part of a project to naturalise peace and cooperation. But I’ve always found it farfetched, and this article seems to agree.

- We Live In An Age Of “Vulture Capitalism”. Interview with economics writer Grace Blakeley. Some interesting discussion about why “state” vs “market” is the wrong debate.

- Watched Into The Congo with Ben Fogle this week. Fogle visits Congo-Brazzaville, and spends time with many interesting peoples and people, including Mbenjele hunter-gatherers, the fashion-loving Sapeurs, and stars of the absolutely bananas Congolese wrestling scene. I have a dear friend originally from Congo (hi if you’re reading!), so it was nice to learn a little more about his country.

- Watched Britain’s Got Talent for the first time in over a decade. Saturday night family entertainment is a thing now, I guess.

- We’ve been laying plywood underfloor upstairs in our house ready to hopefully get some proper flooring soon.

- Final parents' evening of the year was on Thursday. It went fine, despite me being a bit worried about it.

- Made a bit of progress toward my next crossword for mycrossword.co.uk. I’ve not set one for months, and they take me so long to construct.

-

It’s quality time with your child. I work too much at the moment. After work, it’s a mad rush to get everyone fed and to bed (before resuming work, natch). On the average weekday, quality time with the little one can be in short supply. But embedding bedtime stories into our routine all but guarantees my son gets my undivided attention for at least 15 minutes — and this is the last thing he experiences before settling to sleep.

-

It’s a ritual. As Ted Gioia recently reminded me, rituals are part of the antidote to our modern culture of overwork and hyperstimulation. The importance of ritual in the Good Life goes back to Confucius. Rituals are about creating “sacred” contexts in which the ordinary habits and roles of life are put aside, and attention is devoted to observance of the ritual. The repetitive nature of a ritual is part of the point.

The bedtime story is a ritual. The everyday distractions — for me, digital devices; for my child, toys — are put away. We adopt the roles of reader and listener, cuddler and cuddled. My child knows instinctively that something special is happening when we sit down for bedtime stories. It is our developed grown-up brains that rationalise it into something else.

-

It’s a performance . The most effective way to prevent reading the same story over and over to your child becoming boring and stale is to think of it as a performance. Tonight you won’t just be reading The Gruffalo to your child; you’ll be giving him or her the best reading of The Gruffalo they’ve ever had. My reading of The Gruffalo kicks ass, and no, I’m not bored of it. Play with intonation. Do silly voices. Play games with the words and illustrations. Whatever it takes to delight them.

-

Your child will surprise you. Young children change so rapidly, yet in our busy and distracted world we often miss the little things that change day-to-day. But in the quiet of the evening, during the ritual of the bedtime story, we have an opportunity to witness these little changes. If you pay attention to what they pay attention to, the illustrations they point out, the connections they make, your child can surprise you over and over again. And the more you read to them, the faster they learn. You’ll get back what you put in, if you allow your child to show you.

-

You’ll inspire them to love books. If you make books loveable, by turning reading into a special ritual with a performance that delights them, then your child will love them. Despite all his cool toys and light up and make noises, my boy is captivated by books, and he can’t even read them yet. He picks up books of his own accord and repeats the words he can remember from each page, and searches for his favourite things in the illustrations. With any luck, this is the first step to a lifelong love of reading.

Yelling at clouds

In Volume 1, Chapter 1 of Capital, Marx describes how commodities appear on the shelves as if by magic, obscuring the underlying material realities of the production — who made them, under what conditions, using what technologies, and why are they priced that way. Here in the 21st century, there is another kind of product Marx could never have foreseen that masks its material nature even more. A traditional commodity at least has an obvious material form. But our digital devices increasingly depend on something we don’t see: “the cloud”.

Our devices gain new computational powers in a way that seems magical, but this is an illusion. The “magic” happens on a machine in a hyperscale data centre on the other side of the world. These massive facilities contain tens of thousands of computers, and consume vast amounts of energy and water. They have real impacts on the people working and living near them.

While this model may be more efficient than having many small data centres, efficiency isn’t the full story. First of all, the overall energy and water needs may be overall lower per gigaflop of computation in hyperscale data centres. But the impacts of the hyperscale data centres accumulate in concentrated areas. Meanwhile, distributing the energy and water needs across small data centres over a larger area may cause less harm by not putting any one locality at risk of blackouts or water shortage.

But moreover, in condensing into fewer hyperscale data centres, we’re talking about concentration of capital (specifically cloud capital, as Yanis Varoufakis calls it in Technofeudalism). This gives the owners of the data centre power over others. Local and national governments are bending over backwards to appease the big three cloud companies (Amazon, Google, Microsoft) and allowing the expansion of data centres, often against the wishes of local citizens. Because cloud capital acts as essential infrastructure, companies and institutions all over the world are increasingly dependent on three massive American tech companies,a significant advantage to the US geopolitically.

This concentration of cloud capital gives tech companies the power to increase demand for cloud computation. The AI craze is the latest frontier: Microsoft, Amazon and Google are quite happy to invest heavily in AI R&D in part because it increases demand for data centres. By aggressively integrating computationally-intensive AI into consumer applications and the backend services they offer companies, demand for cloud capital grows.

The growth in demand has significant climate impacts. Growth in cloud computing is offsetting progress on renewable energy. Data centres are either sucking up all the newly commissioned renewables that could be used to power homes and businesses, or their presence is preventing the decommissioning of fossil fuel infrastructure. Google and Microsoft have essentially abandoned their emissions ambitions in pursuit of AI.

Data centres may well become a frontier of anti-capitalist and environmentalist struggle in the years ahead. Ultimately, we need to have a conversation about the rapidly growing demands of highly centralised large-scale cloud computing, and the underlying models and assumptions that create demand for them. AI is one obvious technology that must be reckoned with, but the data-hungry “surveillance capitalism” business model has been with us for a long time. Storing and processing large amounts of data has become so cheap that little thought is given to it in the design of applications and platforms. And yet it all has an impact.

Anyway, this post is really preamble to a podcast recommendation: Paris Marx’s Tech Won’t Save Us podcast is doing an excellent 4-part series of 30 minutes each on data centres and their impacts called Data Vampires. Start listening here or in your podcast app. The two other materialist anti-tech podcasts I recommended in a previous post — Trashfuture and This Machine Kills — have both had interesting and entertaining discussions with Marx about the new series, with TMK taking an interesting anti-imperialist angle.

Going part-time to work full-time

In the UK, teachers work the most unpaid overtime of any profession. 40% of teachers do an extra 26 hours a week. More than half of teachers are working more than 50 hours a week — some up to 70. These numbers vary from school to school, subject to subject, department to department, but they’re not helped by the fact that schools are expected to do more with less. Over a decade of austerity, Covid, and a massive increase in energy bills have left many schools on a shoestring.

I’ve certainly felt myself on the rough end of this. For the first two years of my teaching career, I was in a mess, working every night until late in the evening, as well as at weekends. It wouldn’t surprise me if I were in the 40% mentioned above. I like my school and my colleagues, but my department lacks centralised planning and resources (those that do exist are generally very old, some relying on obsolete software), leaving me to start from scratch every day. And that’s alongside the marking, mandatory training, parents evenings, and everything else a teacher has to fit in. I was struggling with stress, anxiety, and depression, and looking for work outside of teaching.

That never materialised, but this year I’ve returned to work on one less day a week. Far from a day off, this is my one chance to get my work done for the week at a sensible time — 80% the teaching workload, and about three times as much time available to do it. I’m one of the many teachers accepting part-time pay to sustain a full-time lifestyle. The difference it has made so far has been extremely noticeable. For the first time, I’m usually a few days ahead on my planning. And I’m actually able to be present and care for my children in the evenings.

This year, we did acquire some half-decent resources for our KS4 curriculum, and that too has made a significant difference. The next step will be to push for my department to invest in some good shared resources for the rest of the curriculum. Who knows, maybe one day, half my day off will be an actual day off.

Never click through to anything that might improve your life

Much as I avoid most of traditional social media, there’s one platform I still spend a significant amount of time on: YouTube. Video essays (YouTube’s original art form), in-depth interviews, and niche documentaries are, for better or worse, a big part of my media diet.1 I should probably just subscribe to Nebula, since most of my favourite creators are there anyway, but I’ve not got round to it yet.

I was browsing YouTube on my TV yesterday, and a video popped up in my recommendations:

“Why your toddler won’t listen to you and how to fix it”

I am currently having real difficulty with my toddler not listening. He’s very good at the “selective hearing” thing, choosing to ignore his mum and I when we need him to do something like brush his teeth. He also very easily gets worked up into a state and won’t listen to us even when we’re trying to help resolve his problem. And sometimes he acts up and doesn’t listen when we say “no” or threaten a sanction. This is all very standard toddler stuff, obviously. It’s just trying on my patience when we’re also trying to look after a <1-month-old.

I know why this video popped up in my feed — about a week ago I’d tried to find a silly video or song to make toilet training more fun for him. The Algorithm now “knows” I have a toddler.

My selection hovered over it for a moment. Maybe this video would have some useful advice. I’ll never know, because in that moment a preview of the timeline I’d enter were I to click that video unfolded before me in my mind.

It’s the same old story with so many of my interests and hobbies. I look at that one video, perhaps even with a very specific purpose in view. Take fitness, for example. It is quite plausible that the deluge of fitness-related videos in my YouTube recommendations feed originates with one innocent time that I searched “how to deadlift” or something like that. An innocent place of ignorance. Now I am overwhelmed with content. Mistakes to avoid. Maximise your gains with this one simple trick. The pros and cons of shoulder pressing. Why I should be carrying a sandbag over long distances through the woods (not joking). It’s the same story with photography, programming, productivity, climbing, etc.

To be clear, it’s not the videos offered are always useless, or the creators don’t know what they’re talking about (though often, it’s very much this). Many of the videos and creators are good. But that’s not the problem. The Algorithm takes the innocent ignorance of the beginner and offers enticing solutions from all directions, with clickbait titles and thumbnails. Many of the ideas presented contradict each other. And the information overload comes with a kind of anxiety that can get in the way of learning through experience. In other words, YouTube’s recommendations is one of the least helpful ways to present (potentially) helpful information.

I knew that if I followed that link to the parenting video, that would be that. I’d condemn myself to drowning in a stream of strangers and their opinions of how I should parent. Contradictions, fads, good and bad advice all presented with titles and thumbnails designed to bypass all my critical faculties. For something as intimate as parenting, I don’t want a throng of wannabe parenting gurus trying to tell me how to do it.

YouTube has some great stuff, but maybe it’s worth avoiding the recommendations algorithm. One solution is to subscribe to channels I actually want to see via RSS2. And perhaps it’s best to avoid clicking videos that claim they will improve your life, unless you want to endure months of being offered hundreds of videos that might improve your life.

Blaugust farewell

Blaugust2024 is coming to its close. This was my second blogging challenge — the first being micro.blog’s April photo challenge (see all entries or my entries). The challenge of writing something daily was much harder than mbapr, for which I had my photo archive to fall back on as well as the means to whip up new entries relatively quickly. Moreover, in mbapr, the prompts for each day are provided.

I kept up daily posting until the birth of my second son. And I found it really tough. Even shaping my more-or-less off-the-cuff posts into something vaguely readable often led me to staying up later than intended. I mean, shit, it’s not like I posted anything deep or well-researched. Writing is just hard. When my child was born, keeping up the posting was impossible and to be honest, the way it’s going, I expect it’ll be this way until he actually has a reliable bedtime. But that’s fine with me — something would be wrong if it were any other way.

From Blaugust, I’ve learned that daily (or even near-daily) posting is not for me. However, a manageable daily writing practice may well be, perhaps following some of the advice from this site. I’d definitely like to move more toward quality than quantity and push myself with my writing.

As I heard from several Blaugustians at the start of the process, the real joy of Blaugust from previous years is the community, and I’m pleased to be able to validate that. The active Discord server, the Mastodon hash-tag, the various livestreams… a very inclusive and encouraging community. A big thanks to Belghast and his team of Blaugust “mentors” for making it happen. I’d planned to make more posts more specifically engaging with fellow participants as the month went on, but then (new) life happened. I’ll be sticking around the Discord anyway, so I’m sure I’ll get around to that at some point…

Anyway, my site doesn’t have a guestbook or comments (yet), but if you’re reading this and have checked out my site at some point during Blaugust, I’d love to hear from you, even if you have nothing to say other than “hi”. You’ll find an email link at the bottom of this post (if you’re reading from RSS or my site’s homepage you might have to click through to the actual post)

See you all again for Blaugust2025 (but hopefully sooner than that)!

Three critical tech podcasts

It’s creator appreciation week here in Blaugust-land. Yesterday I suppose I was appreciating Brian Walker. Today, some podcasts.

Capitalism has provided us with a tech industry that seems to lurch from stock buybacks to mass layoffs, bounce from hype-bubble to hype-bubble, and involves billions of VC dollars propping up unprofitable companies, while promising it’s in the process of delivering a high-tech utopia. Mass surveillance, worker exploitation, and downrights scams are baked into the business models.

Here are three excellent podcasts that critique these tendencies of the tech sector from the left, often taking inspiration from the Luddites (who were not against technology per se, but against the wealthy using techmology to dominate ordinary folks). All three podcasts occasionally have each other as guests.

Have you played Brogue?

I don’t post about games very often (though I do play them a lot), but since Blaugust originated in the gaming community I will talk about a relatively obscure game I like.

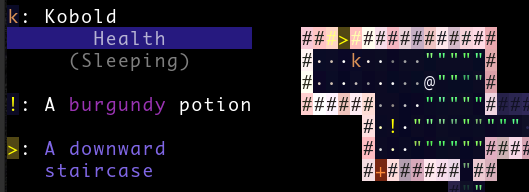

Brogue is a traditional roguelike originally developed by Brian Walker. A “traditional” roguelike is a turn-based RPG played on a procedurally-generated grid, where the player has only one life. Walker no longer maintains Brogue, but the “community edition” has continued to improve the game with bug, balance, and quality-of-life fixes.

While most traditional roguelikes are part of a long lineage, building on predecessors such as Angband and Nethack, Brogue takes its primary inspiration directly from Rogue. It’s aiming to be Rogue with modern design principles.

As the genre evolved to be played on a text-based terminal, ASCII “graphics” were the norm, a tradition carried on by many modern roguelikes including Brogue. In this article, I’m going to try and convince you to try a game that looks like this:

Forgive me if I have to a ramble about its virtues a little too hard; I can’t exactly show you pretty screenshots.

As in Rogue, the hero must enter the dungeon, descend through 26 levels, acquire the Amulet Of Yendor, and then return to the surface in one piece. A simple enough premise — let’s talk about the gameplay and design.

Reflecting on 10 years of veganism

This month I will have been vegan for 10 years.

How it started

Probably around about 2012 I began to feel bad about eating meat. I tried vegetarianism, but ultimately failed. For one, I was working in a pub kitchen and cashed-strapped. Being able to eat scraps of meat that would otherwise be thrown away was a small perk of the job. But the other reason was that I found vegetarianism too contradictory, knowing that the dairy and egg industries were hardly kind to animals either and — since only female animals produce eggs and milk — deeply intertwined with the meat industry. I perceived veganism to be too difficult and extreme, so to resolve the tension I ended up just eating meat again. I guess the psychology is interesting and fairly common — lots of people I speak to feel reducing animal harm has to be all-or-nothing.

In 2014, I’d just moved to Liverpool to begin my studies, and I generally felt in a mood for new beginning. My journey into veganism began when I started following the comments of a belligerent vegan advocate on Reddit. He showed up in any thread about animals and began arguing with anyone with an opinion about eating meat, and often appealed to his master’s degree in ethics. He was probably everyone’s stereotype of an annoying vegan, but I could not get around the strength of his arguments.

At one point he said “If you claim to care about animals but still eat them, then maybe you’re just a shitty weak-willed person”. Again, a rather abrasive style of argument, but I could not really refute this. I did think it was wrong to eat animals given I could be perfectly healthy without them, and yet I was eating them every day.

Stoicism vs existential commitment

The Stoics, especially Epictetus, teach about not allowing anything that is not under your direct control to have the power to cause you pain. This means not becoming attached to “externals”, as only things internal to us — our thoughts and intentions — are under our control. If we cease to identify our wellbeing with things outside our control, we can be happy.

However, there are certain externals that I assent to causing me pain. I want them to have the power to cause me pain. For example, the death of a family member. According to Epictetus, it is not something I control, so it should mean nothing to me. This is not a reductio ad absurdum against Epictetus — he literally says

If you kiss your child or your wife, say to yourself that this is a human being […] and then, if one of them should die, you won’t be upset.1

By reminding ourselves that that this is a human being, we are supposed to remind ourselves that they are fragile and this fragility is beyond our control. This is right after advising us to remember that the pottery we like is fragile.

Most of us instinctively reject this. If we are not allowing the death of a loved one to cause us pain, in what sense can we say to be loving them? Isn’t the commitment to caring about someone’s life an integral part of love?

This is a central concept in Marten Hägglund’s This Life. For Hägglund, what gives our life meaning is secular faith, which could be briefly defined as “deep devotion to fragile things” — our own lives, the lives of loved ones, projects, moral and political causes. He describes vulnerability to grief as “a common denominator of all forms of secular faith”2. Hägglund’s project is to argue that is it is secular faith, not faith in eternal or unbreakable things, that gives our lives meaning, and from there develop political implications.

The Stoics have a lot of wisdom and advice for detaching yourself from external things that do not matter, rejecting unhelpful thoughts and emotions, and becoming a better person. But I think Epictetus misses the mark with his instruction to detach from all externals; there are some externals I willingly surrender my invulnerability to because they define the meaning of my life.

The horror of teeth

CW: teeth, death

I have always had a mild anxiety about teeth, which I imagine is commonly felt. Unlike other body parts, teeth do not regenerate or heal. They only wear over time, and sometimes break; the damage is permanent. The state of my teeth is a constant reminder of my mortality, that I am a decaying thing and, once my heart stops beating, the rest of my body will meet the same fate as my teeth.

Every filling, chip, and extraction (yes, my teeth aren’t great) brings this process further into relief. The moment a tooth is damaged or drilled I am filled with dread, a sense of irretrievable loss.

I think this is why tooth-loss dreams are so common. They’re an anxiety about losing something irreplacable, perhaps one’s own life or that of a loved one.

Reflecting on one’s own impermanence and mortality is not necessarily a bad thing. It can be motivating, and a reminder to treasure what you have now. Memento Mori (“remember you must die”) is a recurring motif in art and philosophy, often accompanied by the image of a skull, teeth by-necessity bared.

Strangely, this perception may be soon tbe challenged by modern technology. New drugs and therapies are in development that effect the regeneration of teeth, which seems like magic to me. Future generations maybe regard broken teeth like broken bones.

Rucking along

While I’m lucky that my job as a teacher means I’m not usually simply sitting down all day, I’ve always struggled to find the right cardio for me. Swimming is too much hassle. Cycling on these country roads with cars going up to 60 mph feels too dangerous. And I just never could get into running. So while this year I’ve started to take strength more seriously, my cardio health had not been given much love.

That is, until the last few weeks, during which I’ve “discovered” rucking from trainer winny. It’s a simple premise. You put something heavy in a rucksack and then go for a brisk walk. It’s far from a new idea — soldiers have trained in this manner since forever. But in the last decade or so it has surged as a fitness exercise for civilians too.

The advantages of rucking as compared to other cardio activities for me are:

The only real rules seems to be to start small and work up. Ideally the weight should be as close to your back as possible, and high up. Maintain good posture with an open chest — don’t hunch over. You can modify the exercise to your needs by varying the weight, distance, pace, and gradient of the walk.

For me, I’ve settled on 10kg (+ towels), and a fairly hilly 45-minute walk to the nearest village and back, about 3 miles total. The different inclines give me a nice burn in different parts of my legs, and the 10kg feels about right that I’m feeling the benefit but not risking any injury. Usually I’ve not taken my phone, but last time I brought it for some relaxing music. I think I’ll stay away from podcasts though, as part of the value is that mind-wandering time.

Having said all this, I do see the funny side of modern fitness content creators (and me, in this post) promoting the radical idea of going for a walk while carrying something. For all the complex training programmes and exercises out there, sometimes simple really is the best.

Let's just have less

Many AI critics have pointed out the environmental cost of LLMs. The rapid expansion of data centres, running energy-intensive operations such as training, have led to Google’s emissions jumping by almost 50% in the last 5 years, with similarly high figures for other AI companies.

Defenders of these companies point out that renewables and nuclear will be deployed to meet this energy demand, as well as making the (frankly implausible) claim that LLMs will contribute to new ways to reduce emissions.

Critics have several responses. The first is to point out that here in the present, AI is being powered by fossil fuels — and in at least one case, a coal plant has had its decommissioning postponed due to AI energy demands. Second, renewables aren’t free — they require land, labour, time, and resources to construct. If renewables in some area are simply going to power rapidly expanding AI data centres, then they’re not meeting the existing energy needs of that area — so everyone else will be left continuing to use fossil fuels.

Moreover, efficiency improvements in AI technology can’t solve the problem. Jevons' paradox points out that efficiency gains often lead to higher total consumption of a resource, because greater efficiency = more bang for your buck = higher demand.

AI is not currently providing many benefits for many people — sure it’s helping some people write email more efficiently, and it is assisting some programmers. But most people don’t use AI, and don’t have a use for AI. All AI is doing for them is putting more spam and fake news into their feeds, and making search results worse.

So the obvious way to bring down the emissions from AI is less AI. We don’t need it. Many (most?) of us don’t want it. And if the market doesn’t bring about this change, then we can use policy.

But why limit this critique to AI? There are plenty of industries providing very limited social benefit while being environmentally destructive. These sectors are competing with the more socially necessary ones for the same energy and materials, using up renewables and preventing the decommissioning of fossil power. A big part of the solution is less of the bad stuff, rather than trying to outpace its growth with renewables.

My life through 6 possessions

The theme for this Blaugust week is “introduce yourself”, but I didn’t really want to just do a standard “About me” post. I decided instead to share some treasured possessions of mine that say a bit about me. Since each possession came with its own little story, this post has ended up being rather long!

Each item represents a different phase of my adult life, and I’ve tried to order them roughly in order, so it’s kind of a biography. But since these are treasured possessions, it’s quite a one-sided, only-the-nice-parts biography — not that I haven’t been very fortunate; I have.

GameCube controller

The most important gaming community I have ever been involved with is the UK’s Super Smash Bros. Melee tournament scene.

Why blog? Why this blog?

When I tell a friend about this young site, they’re usually surprised. Who has a blog these days? But they can also see the appeal. Mainstream social media did not deliver the goods in the long run, and while most people still use it in some form, they do so with some begrudgement, perhaps knowing the arrangement between them and the platform is not what they’d choose in an ideal world.

I did the social media thing too, of course. As a teen I had MySpace and think I may even have done some cringy teen blogging on there (cringy teen blogging definitely happened, question is where). Then from MySpace to Facebook, which I quit in 2016. I’d wanted to for a while; I was outraged by the Snowden revelations, and also I don’t think I liked the way it encouraged being “Friends” with… well, everyone you knew, once knew, know someone they know, once met while drunk, … I think it was reading Deep Work that finally got me to quit.

After quitting Facebook — and Twitter a bit later during the fierce polarisation that occurred after the Brexit vote — I was happy without social media for a while, but I still wanted some kind of online presence. I tried a short-lived blog about my mathematical studies (thetangent.space, which is a great domain name for a maths blog… maybe I should move back there with this blog…).

At some point I heard about the IndieWeb and liked what I was reading as a real alternative to social media. I didn’t feel I had the time to learn the technical know-how to create a blog that implemented some of the IndieWeb protocols, and it was only when I learned about micro.blog (an indieweb friendly plug-and-play blogging platform) that I finally took the plunge and started this blog, which is my most successful — in terms of longevity and volume of posts — blogging attempt.

So back to the title: why blog? For me, having a personal website or blog is about having “my space” without a MySpace. The stuff I put out on here is for me and anyone else who is interested, not for an algorithm that sees my posts as raw-material (“content”) to weave into timelines to keep that ad-revenue flowing.

In fact, this space is self-consciously in opposition to the attention economy. I’m not trying to gain revenue, create a brand, or display any ads. I collect no analytics. The closest thing I have to self-promotion is linking to the crosswords I construct on MyCrossword. This is the kind of web I want — people connecting as people, not in service of brands and algorithms.

It’s also to push me to be a better writer, and with that a better thinker. A lot of what I post is trivial, and doesn’t represent growth in my writing. But that’s okay. In fact, it’s great. I’ve always shied away from writing publicly because it’s scary. People will judge me and my writing. But the trivial posts remind me not to take it too seriously. I’m just having fun putting things that interest me out into the world; it’s not that important.

Sure, having a blog takes a little more effort and know-how than having an Instagram. But well, I’m a Linux user. I can deal with a few rough edges and friction in pursuit of digital autonomy, and platforms like bearblog, pika, scribbles and micro.blog make it pretty straightforward whatever your level of technical ability. Get a blog, start posting, and be part of the web you want to see.

Welcome to Blaugust

So here we are, ready to kick off the Blaugust festival of blogging. If you’re visiting my site for the first time via Blaugust, then welcome! If you’ve been here before and would like to join in, then there’s still time to sign up here; if you don’t yet have a blog and want to join in, I made a guide to getting started here. This post has links to a list of other participants' blogs and an OPML file for your feed reader.

I’m Sam. I am a 32-year-old husband and father, and I teach secondary mathematics in the UK, though this is a strictly personal rather than professional blog. I post about books I’ve read, things I like, parenthood, my political views, links with commentary, and so on. I’m an unfussy coffee drinker, and rubbish at social media.

There’s more to say, of course, but I’ll save that for next week — the Blaugust theme is introducing yourself.

From Blaugust, I’m hoping to improve my own writing practice, and connect with other writers and readers. Please do get in touch if you’re reading — e-mail, Mastodon, the Blaugust Discord, or even a reply blog post are all welcome. I’m not expecting to hit 31 posts in Blaugust, but I’m going to aim in that direction. Better to aim for 31 and post 15 times than aim for 5 and post 4 times.

In terms of what to expect here, I’ll be loosely following the “official” themes of each week, trying to get at least one or two themed posts per topic. As Blaugust started on a gaming blog and many participants seem to be games bloggers, I might publish a couple of posts about games.

Finally, I should note that at some point during Blaugust, I’ll be having my second child 👶, so who even knows what will happen at that point.

Join me for Blaugust

In an effort to improve my posting frequency and get out of a rut, I’ve signed up for the community blogging challenge Blaugust, a blend I’m presuming works better with an American accent.

The premise is simple. Just post as much as you can in August. It doesn’t have to be every day, but just post a lot. There are optional themes and prompts for each week, as well as optional “blaugchievements” (the guy who came up with this challenge seems to have a real vendetta against the English language), and ways to connect with other participants.

Consider this post a gentle nudge to join me, whether you already have a blog, or you’ve been half-thinking of giving it a go (I’m looking at you, IRL family and friends who think it’s cool (?) that I have a blog but don’t have your own!)

If you’re interested in giving it a go but don’t have a blog yet, here’s my dead simple guide to getting started.

Please do let me know if you decide to join in with Blaugust so I can follow your posts.

The olive oil shortage may be just the beginning

Olive oil’s return to being a luxury item heralds a new era of bland cooking Everyone I know has been shocked by the price increase of olive oil, which has more than doubled in the last two years. It doesn’t feel like long since I was picking up a litre of extra virgin olive oil from Aldi for under £3. It’s now almost £7. “Proper” brands are now more expensive than wine. I’ve more or less stopped buying it. Maybe I’ll get it as a treat sometimes.

It’s a feeling we are not particular used to as a culture — a good going from abundant and commonplace to scarce and luxurious. There have been fluctuations in the price of fuel and energy over the years — but these are usually due to temporary political situations. We are used to goods generally getting more abundant, and for price rises to be relatively small, and often temporary.

This feels different. It feels frustrating. Olive oil has been so available that yes, I do feel slightly entitled to it. That olive oil is healthy rather than a vice adds to the indignation. The feelings are not particularly rational.

I’ve been reflecting on these feelings, and also the very real possibility that this change is permanent. There are several reasons for the shortage — extreme dryness in growing regions, and an outbreak of disease that has led to the destruction of entire plantations of ancient olive trees. With the world only continuing to get warmer and drier, we may not ever get affordable olive oil again. It’s a sobering thought.

With the multiple overlapping ecological crises we face, this is unlikely to be the last time this happens. Food insecurity is forecast to increase. We may have to get used to a world where another everyday foods falls off the menu every few years. If the extreme weather we’ve been seeing hasn’t yet led to mass action on climate, perhaps the threat to our dietary diversity will.

Farming animals is a threat to us all

Rise of drug-resistant superbugs could make Covid pandemic look ‘minor’, expert warns

Antibiotic misuse and overuse threatens to leave us in a post-antibiotic world. Antibiotics are not only essential for curing illnesses, but also to protect against wound infection — including surgical wounds. Routine, safe surgeries could become life-threatening.

The burden for reducing antibiotic use currently falls overwhelmingly on medical and healthcare workers. Yet the majority of antibiotics used worldwide are used on farmed animals. They are used en masse to prevent (not cure) infection in unsanitary conditions, as well as to promote rapid growth.

Most antibiotics used by humans and animals are excreted, ending up in fertiliser, in our rivers, or in our sewage. In other words, our food and water systems become breeding grounds for antimicrobial resistance. Moreover, the primary mechanism for the spread of antimicrobial resistance is via horizontal gene transfer — the tranfer of genetic material between species, even distantly related ones. Even if antimicrobial resistance evolves first in pathogens affecting animals, those adaptations can be passed on to pathogens affecting humans.

Animal farming is bad for animals, the planet, and poses a risk to the future of medicine. Cutting down the use of antibiotics in farming is likely to decrease animal welfare due to disease, and organic farming dramtically increases the land (and hence ecological) footprint of rearing animals. In the majority of the industrialised world, there’s no “good” way to do animal farming.

Weekly Digest

Trialing a new format.

Links

This week we have a bunch of lefty links.

Reading

Roadside Picnic by Arkady & Boris Strugatsky. Gripping Soviet-era sci-fi novel that the Stalker film and S.T.A.L.K.E.R games are based on.

Listening

The Airborne Toxic Event by the band of the same name. I’d not listened to this band in years. Brilliant album, with the standout track Sometime Around Midnight being one of the best sad songs of the 00s.

Watching

Up to much else?

A little knowledge can enrich so much

Today my wife and I took our little one on a walk through the fields and woods near our house. Having only recently moved to this area and having lived mainly in cities as an adult, this is still quite a novelty. It was a lovely walk — our just-turned-two-year-old managed to go for over 90 minutes. I think he complained less than me.

It was even more enhanced by the wildlife we saw. This included a field mouse, a muntjac, and several birds, including goldcrests and jays. A week ago I could not have identified a goldcrest, and until today I could not have identified a jay. But my wife has recently been reading Be A Birder by Hamza Yassin, a beginner’s birdwatching book. She’s since been telling me things about birds and my interest in and knowledge in them has increased. And so on this walk, I was amazed at how much even the most rudimentary knowledge of birds enhanced the experience. I now know the names and at most one fact about some birds (beyond stuff like pigeons and blackbirds), and it was so much more fun than just thinking “oh look, a bird”.

Another time I have had this experience was after listening to the audiobook version of the Great Courses' How To Listen To And Understand Great Music (unsurprisingly a course that does perfectly fine in audio format). While the course touches on many key developments in western music, at its heart is the classical symphony, with particular focus on the sonata-allegro form, a musical structure that appears once or twice in virtually every classical symphony and concerto. Whatever comes to mind when you think “classical music”, from the Beethoven’s 5th or Eine Kleine Nachtmusik to any of Haydn’s hundred-odd symphonies, it’s probably following a standard structure that includes the sonata-allegro form. Learning just this from this course has enhanced my enjoyment of pretty much every symphony. Plus, the lecturer is a hoot.

I often tell my students when they ask something like “Why do I need to know the ratio of a circle’s circumference and diameter?” something like that “You see circles every single day of your life, do you not think you should know the most elementary thing about them?”. I see birds enough times that it’s worth knowing the first damn thing about them, too. Because the basics are, well, basic, you can learn a lot of them very quickly, the cognitive equivalent of “noob gains”. It’s delightful how little it takes to enrich your experience — just some curiosity and a well-made beginner’s guide.

The Joy of Reading to a Child

At one time in the past I was browsing Reddit and stumbled on some thread where Redditors were doing what they do best, which is complaining about the existence of children. In this instance, the particular grievance was that children require reading to, and children’s books are boring, especially when you’ve read them a hundred times already. The Gruffalo was given as an exemplar of a boring children’s book.

Well, I’ve been reading to my child for months now and I’m sure I’m reaching the hundred mark with some of these books — possibly including The Gruffalo. I can safely say these Redditors were missing the point (say it ain’t so!).

I’m sure you, dear visitor, are better-adjusted than the average Redditor and don’t require convincing that reading a child a bedtime story is actually quite a nice thing to do. But let’s celebrate the joys of this simple habit regardless.